Is February 2026 a Leap Year? The Definitive Guide to Our Calendar’s Rhythmic Dance

Ever found yourself staring at a calendar, wondering about the future, especially when it comes to those quirky leap years? You’re not alone. Many people want to know if February 2026 will be a 28-day sprint or a 29-day marathon. Let’s cut straight to the chase:

Table of Contents

- Is February 2026 a Leap Year? The Definitive Guide to Our Calendar’s Rhythmic Dance

- The Quick Answer: Why 2026 Isn’t a Leap Year

- Understanding Leap Years: More Than Just an Extra Day

- What Exactly Is a Leap Year?

- Why Do We Even Have Leap Years? The Cosmic Mismatch

- Unpacking the Rules: How to Identify a Leap Year (The Gregorian Algorithm)

- The Primary Rule: Divisible by 4

- The Century Exception: Not Divisible by 100… Unless…

- …Divisible by 400

- Looking Ahead: When Are the Next Leap Years?

- The History Behind Our Calendar: Julian to Gregorian

- The Julian Calendar: Caesar’s First Attempt

- The Gregorian Reform: Pope Gregory XIII Steps In

- Common Year vs. Leap Year: What’s the Difference for You?

- Day Count and February’s Length

- Planning and Scheduling Impacts

- Myths, Traditions, and Fun Facts About Leap Years

- February 2026: What to Expect

- Conclusion

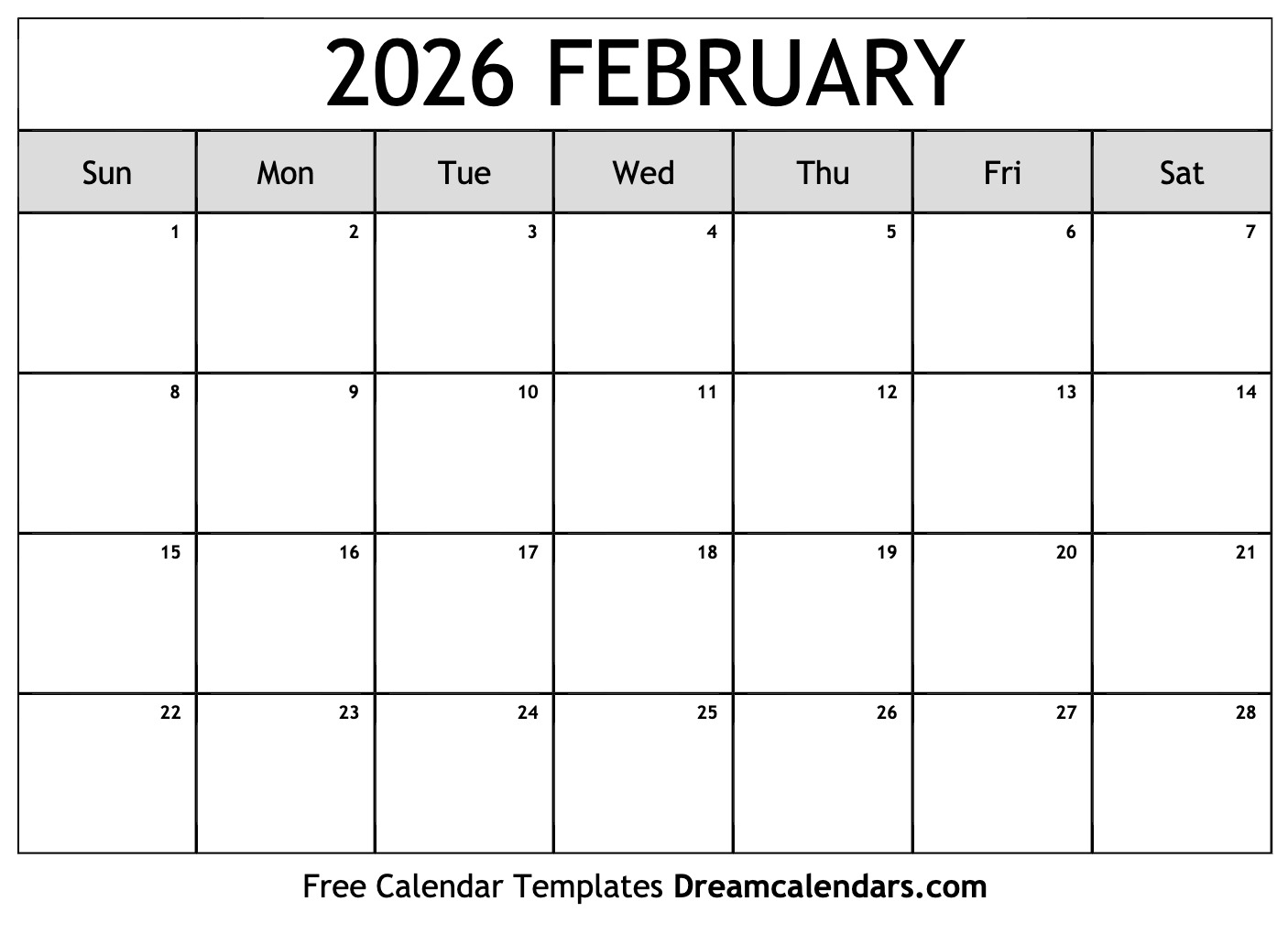

No, February 2026 is NOT a leap year.

This means your February in 2026 will have its usual 28 days, and the year itself will be a standard 365 days long. The last leap year we experienced was 2024, and the next one won’t roll around until 2028. But why is that? And what even is a leap year beyond just an extra day?

This guide will demystify leap years, explain the fascinating science behind them, help you identify future leap years, and clarify exactly what to expect from February 2026.

The Quick Answer: Why 2026 Isn’t a Leap Year

When it comes to leap years, there’s a specific set of rules (thanks, Gregorian calendar!) that determine which years get an extra day. The most basic rule is that a leap year must be divisible by 4.

Let’s do the math for 2026:

- 2026 ÷ 4 = 506 with a remainder of 2.

Since 2026 is not evenly divisible by 4, it immediately fails the primary test to be a leap year. Simple as that! Therefore, February 2026 will proceed with its standard 28 days, just like any other common year.

Think of it this way: 2024 was a leap year, and the next one we’re looking forward to is 2028. 2026 sits comfortably in between, enjoying its status as a regular, 365-day common year.

Understanding Leap Years: More Than Just an Extra Day

While the concept of a leap year might seem like a quirky calendar anomaly, it’s actually a brilliant solution to a cosmic problem. It keeps our human-made calendars aligned with the fundamental rhythms of our planet.

What Exactly Is a Leap Year?

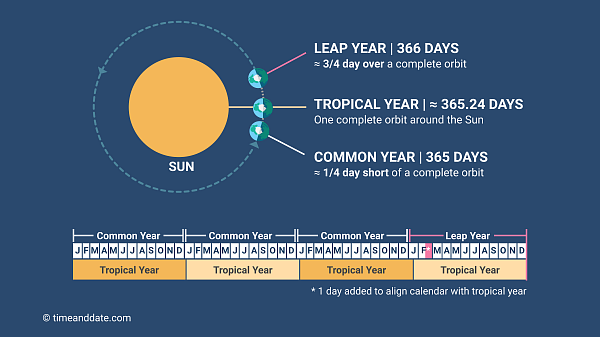

At its core, a leap year is a year with 366 days, one more than the typical 365 days of a common year. This extra day is always added to February, making it 29 days long instead of 28. This additional day, February 29th, is known as a leap day.

Without these periodic adjustments, our calendar would slowly but surely drift out of sync with the seasons and astronomical events.

Why Do We Even Have Leap Years? The Cosmic Mismatch

The reason for leap years boils down to a fundamental incompatibility between how we measure time and how the Earth actually moves. Here’s the simplified breakdown:

- Our Calendar Year: We typically define a year as 365 days.

- Earth’s Orbital Period (Astronomical Year): The actual time it takes for Earth to complete one full orbit around the Sun is approximately 365.2422 days.

See the problem? That pesky extra quarter-day (0.2422 days) accumulates. If we ignored it, every four years our calendar would be off by almost a full day. Over decades and centuries, this tiny discrepancy would lead to significant calendar drift. For example, seasons would gradually start earlier and earlier in the calendar year. Farmers, navigators, and anyone relying on seasonal cycles would face major confusion.

Leap years are our clever way of adding an extra ‘catch-up’ day every four years (with specific exceptions) to keep our calendars synchronized with the true length of Earth’s journey around the Sun. It’s an elegant solution to a celestial challenge!

Unpacking the Rules: How to Identify a Leap Year (The Gregorian Algorithm)

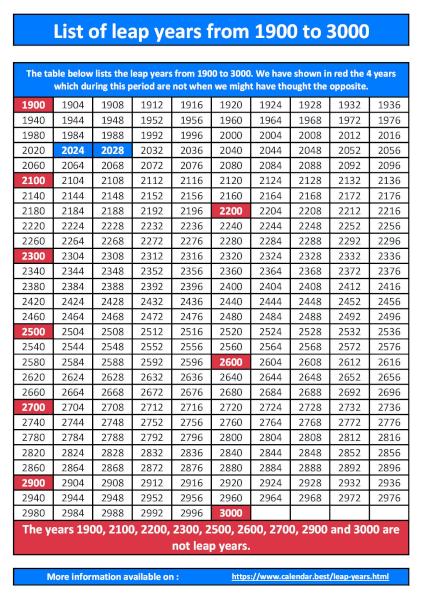

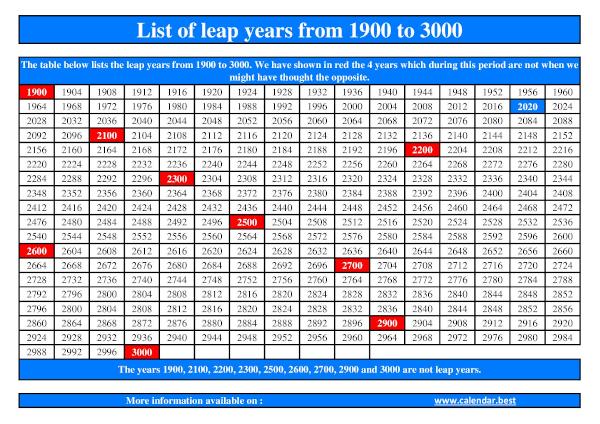

While the ‘divisible by 4’ rule is a great starting point, it’s not the whole story. To ensure even greater accuracy, Pope Gregory XIII and his advisors introduced a more refined set of rules in 1582 with the Gregorian calendar. This is the calendar most of the world uses today. Understanding these rules is key to truly identifying a leap year.

The Primary Rule: Divisible by 4

The first and most commonly known rule is:

A year is a leap year if it is evenly divisible by 4.

For example, 2024, 2020, 2016, and 2012 were all leap years because they could be divided by 4 with no remainder. This accounts for the vast majority of leap years and addresses the accumulating quarter-day problem.

The Century Exception: Not Divisible by 100… Unless…

Here’s where it gets a little more nuanced. Simply adding a leap day every four years is a slight overcorrection, as Earth’s orbit isn’t *exactly* 365.25 days, but slightly less (365.2422 days). To compensate for this minor overestimation, the Gregorian calendar adds an exception:

A year that is evenly divisible by 100 is NOT a leap year, even if it’s divisible by 4.

This means years like 1700, 1800, 1900, and 2100 are (or will be) common years with only 28 days in February. They skip the leap day, despite being divisible by 4. This rule corrects for the small overcorrection of adding a full day every four years.

…Divisible by 400

Just when you think you’ve got it, there’s one more layer of refinement! The ‘divisible by 100’ rule itself is also a slight overcorrection. To fix this, we have a final exception:

A year that is evenly divisible by 400 IS a leap year, even though it’s divisible by 100.

This is why the year 2000 was a leap year, despite being a century year. (2000 ÷ 400 = 5). Without this rule, the year 2000 would have been a common year, and our calendar would have been slightly off again. The year 2400 will also be a leap year for this reason.

To summarize, here’s the full Gregorian leap year algorithm:

- If the year is evenly divisible by 4, proceed to step 2. Otherwise, it is a common year.

- If the year is evenly divisible by 100, proceed to step 3. Otherwise, it is a leap year.

- If the year is evenly divisible by 400, it is a leap year. Otherwise, it is a common year.

Let’s see these rules in action with a helpful table:

| Year | Divisible by 4? | Divisible by 100? | Divisible by 400? | Is it a Leap Year? | February Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | Yes | Yes | No | No | 28 |

| 1996 | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | 29 |

| 2000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 29 |

| 2024 | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | 29 |

| 2026 | No | N/A | N/A | No | 28 |

| 2028 | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | 29 |

| 2100 | Yes | Yes | No | No | 28 |

Looking Ahead: When Are the Next Leap Years?

Now that you know 2026 isn’t a leap year, you might be curious about when the next one will be, or perhaps you’re planning further into the future. Here’s a quick look at upcoming leap years:

| Year | Leap Year Status | February Days |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | Leap Year | 29 |

| 2025 | Common Year | 28 |

| 2026 | Common Year | 28 |

| 2027 | Common Year | 28 |

| 2028 | Leap Year | 29 |

| 2032 | Leap Year | 29 |

| 2036 | Leap Year | 29 |

| 2040 | Leap Year | 29 |

As you can see, after 2024, we’ll have a few common years before 2028 arrives with its extra day. Mark your calendars!

The History Behind Our Calendar: Julian to Gregorian

Our modern calendar, and its leap year rules, didn’t just appear overnight. It’s the result of centuries of astronomical observation and political will, evolving to become the incredibly precise system we use today.

The Julian Calendar: Caesar’s First Attempt

Before the Gregorian calendar, much of the Western world followed the Julian calendar, introduced by none other than Julius Caesar in 45 BCE. Caesar’s astronomers realized the year was roughly 365.25 days long, so he implemented a simple rule: add an extra day every four years. No exceptions for century years, just a straightforward cycle.

While a massive improvement at the time, this ‘every four years’ rule was a slight overcorrection. Over centuries, the Julian calendar accumulated too many leap days, causing it to drift significantly from astronomical events like the equinoxes. By the 16th century, the calendar was about 10 days out of sync with the actual solar year.

The Gregorian Reform: Pope Gregory XIII Steps In

This calendar drift became a major concern for the Catholic Church, particularly affecting the accurate calculation of Easter. So, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII commissioned a reform. The result was the Gregorian calendar, which incorporated the more precise leap year rules we discussed earlier (divisible by 4, except for century years not divisible by 400).

To correct the accumulated error, 10 days were simply dropped from the calendar. Thursday, October 4, 1582, was immediately followed by Friday, October 15, 1582. Talk about a time jump!

The Gregorian calendar was gradually adopted across Europe and eventually worldwide, becoming the international standard due to its superior accuracy. It reduced the calendar’s error to just 26 seconds per year, meaning it would take approximately 3,300 years for it to be off by even a single day.

Common Year vs. Leap Year: What’s the Difference for You?

Beyond the technical rules, how does the distinction between a common year and a leap year actually impact your life or planning?

Day Count and February’s Length

This is the most obvious difference:

- Common Year: 365 days, February has 28 days.

- Leap Year: 366 days, February has 29 days.

Planning and Scheduling Impacts

For most day-to-day activities, the difference is negligible. However, for certain fields and situations, it matters:

- Financial Calculations: Daily interest calculations on loans or savings, payroll for employees paid daily, or contracts specifying a certain number of days can be affected.

- Annual Events: If an event is tied to a specific date in late February, a leap year means it falls one day later in the week than it would in a common year.

- Legal Contracts: Some contracts or statutes might reference specific day counts, requiring awareness of leap years.

- Birthdays: Those born on February 29th (known as ‘leaplings’) only get to celebrate their actual birth date every four years!

Here’s a summary comparing the two:

| Characteristic | Common Year | Leap Year |

|---|---|---|

| Total Days | 365 | 366 |

| February Days | 28 | 29 |

| Leap Day | No | Yes (February 29th) |

| Frequency | Typically 3 out of 4 years | Every 4 years (with exceptions) |

| Astronomical Alignment | Slightly lags solar year | Better aligned with solar year |

Myths, Traditions, and Fun Facts About Leap Years

Leap years have inspired a variety of folklore and traditions over the centuries:

- Leap Year Proposals: In some cultures, particularly in the UK and Ireland, February 29th is traditionally the one day when women are allowed (or even encouraged!) to propose marriage to men. This tradition is sometimes attributed to St. Bridget complaining to St. Patrick about women having to wait too long for proposals.

- Leapling Birthdays: People born on February 29th are often called ‘leaplings’ or ‘leap year babies.’ They technically only have a birthday every four years, leading to interesting discussions about when they “officially” age. Many celebrate on February 28th or March 1st in common years.

- Bad Luck in Some Cultures: In some parts of the world, leap years are considered unlucky for major life events like marriages or starting new businesses.

- Longest Calendar Year: A leap year is, technically, the longest calendar year possible in our system, at 366 days.

February 2026: What to Expect

So, to bring it back to our original question, February 2026 will be a perfectly standard, 28-day month. The year 2026 will be a common year with 365 days. You won’t find a February 29th on your calendars for 2026.

This means your annual planning, deadlines, and holiday schedules won’t have that extra day to contend with. It’s business as usual for our calendar, patiently waiting for the cosmic alignment that will bring us the next leap day in 2028.

Conclusion

Understanding leap years is a fascinating peek into how humanity has strived to synchronize its daily life with the precise, unwavering mechanics of the cosmos. While February 2026 will be a common year, holding its ground with 28 days, it serves as a reminder of the intricate system that keeps our clocks and calendars ticking in harmony with the Earth’s majestic orbit around the Sun. So, enjoy your standard 2026, and keep an eye out for that extra special February 29th when 2028 finally rolls around!

Frequently Asked Questions

Is 2026 a leap year?

No, 2026 is not a leap year. It is a common year, meaning it will have 365 days.

How many days does February 2026 have?

February 2026 will have 28 days, as 2026 is a common year and not a leap year.

When was the last leap year?

The last leap year was 2024, which included a February 29th.

When is the next leap year after 2026?

The next leap year after 2026 will be 2028. You can expect February 29th to return then.

What are the rules for determining a leap year?

A year is a leap year if it is divisible by 4, unless it is divisible by 100 but not by 400. For example, 2000 was a leap year, but 1900 was not, and 2100 will not be.

Why do we have leap years?

We have leap years to keep our calendar year (365 days) synchronized with the actual time it takes for Earth to orbit the Sun (approximately 365.2422 days). Without them, our calendar would slowly drift out of sync with the seasons.

What is a ‘leapling’?

A ‘leapling’ is a person born on February 29th, a date that only occurs during a leap year. They only get to celebrate their actual birth date once every four years.